NBN Statement on the River Ring Project

The North Brooklyn waterfront is now a gold coast, and it should not be. When community activists and neighborhood leaders fought to transform the waterfront from a haven for polluters, they were sold a future with restrained, mixed income residential buildings alongside connected, public waterfront esplanades and parkland.

Instead, the community was inundated with upzonings that supersized many of the residential towers and, to this day, has only gotten a portion of the promised green space and waterfront access. Many of the towers failed to be truly mixed income by offering very few units for families who made less than 80% AMI, using separate entrances for affordable housing tenants (“poor doors”), and otherwise treating those tenants as second-class residents in their own homes.

Waterfront gentrification accelerated speculation and displacement throughout North Brooklyn – particularly on the Southside. In the ten years after the Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning, the Southside lost nearly 1,000 rent-stabilized units according to a 2019 report produced by Churches United For Fair Housing (CUFFH). Yet the influx of new housing has not done enough to meet the needs of existing and long-time residents or replace those affordable units that were lost.

Data from a recent NYU Furman Center shows that only about half of units in Brooklyn Community District 1 are considered affordable to individuals earning $100,000 or families of four earning $143,000 annually (120% AMI). A July 2021 Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD) report reveals that over 11,500 new units were completed in CD1 since 2014 yet fewer than 1,500 of them are affordable.

The combination of lost rent stabilized housing with the trickle of new affordable units has had a disparate racial impact, displacing large numbers of low- and moderate-income primarily Black and Latinx residents. Demographic diversity of the Southside over the past two decades changed dramatically — becoming significantly whiter and wealthier. This continues a trend many decades in the making dating back to the mid-20th century displacement spurred by the construction of the BQE and other urban renewal projects, and widespread building abandonment by landlords that lasted through the 1970s.

Impacts from land use choices over the past 70 years are compounded by our citywide affordable housing shortage, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the climate crisis. The housing shortage is best illustrated by the dramatic population growth on the Southside since 2010. The 2020 Census data reveals that the Southside grew by more than 21% while Brooklyn grew overall by 9.2%. The population surge drives up rents, causes more overcrowding in apartments, and displaces vulnerable residents.

The pandemic highlighted inequities in economic mobility and health access. Many jobs disappeared and industries have fundamentally changed. Families without the ability to socially distance in crowded apartments experienced the worst impacts from the virus. Recovering from the pandemic will take many years and we cannot ignore its lasting effects on our community.

Additionally, Hurricane Ida is just the most recent reminder of the depth of the climate crisis. Frontline neighborhoods and those in flood zones are especially at-risk and need mitigations that prioritize sustainability and reducing harm. Building on the waterfront puts stress on communities most vulnerable to storm surge and sea level rise. These realities require our leaders to promote strategies that consider the long-term viability of every development proposal along with community-wide planning.

We need policy solutions that engage with the complex crises in front of us, address historic harm and inequity, and build a resilient future.

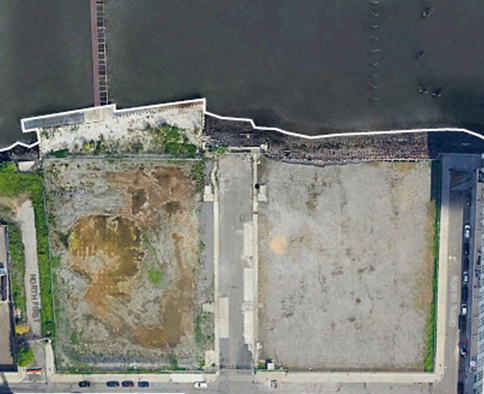

The current proposal for River Ring is anchored by two new residential towers on the waterfront. Back in 2018, before the property was on the mark, we predicted a sale and ULURP application for residential rezoning was on the horizon. In that letter, we identified a number of standards that must be considered in any rezoning request. The current proposal meets many of those standards but times and circumstances have changed and the community needs more – more affordable housing.

The site’s current heavy manufacturing zoning is no longer practicable, but this property should only be rezoned to residential for a project that will better serve the community. In addition, Community Board 1’s recently adopted recommendations identify important concerns about the project and its potential impact on the neighborhood. Each recommendation must be thoroughly considered and addressed as part of this process.

We challenge Two Trees to do its part to do more for the neighborhood’s much needed affordability. The gap between the number of market-rate units and affordable units must shrink and be more deeply affordable. We believe a project where half of the units are permanently affordable, at an average of 40% AMI, is an important commitment to the future of the community. The median household income for the Southside ($61,493) is less than 60% AMI for a family of 4 ($71,580) meaning that affordable units at or above that level will remain significantly out of reach for the typical family on the Southside.

If ULURP is truly supposed to be the time to hear and incorporate community feedback and priorities then there is still time for vital changes to be made to the project – rather than trying to race across the finish line. We must make this project more deeply affordable across a greater number of units.